|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

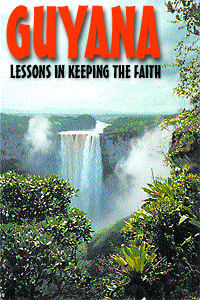

Vast Kaieteur Falls dominates the horizon. Catholic New World photos by Michael D. Wamble |

|

By Michael D. Wamble

Staff Writer

During a three-week period this winter, Catholic New World staff

writer Michael D. Wamble participated in UCIP University 2000,

an international program for journalists and members of the Catholic

press to study abroad. Wamble spent each week in a different Caribbean

country. This report is from Guyana.

On eagles’ wings

We began to plunge. The tiny twin-engine plane sank toward the

ground like an anvil in the ocean.

“Are we landing?,” asked Father Christopher Bologo, editor of

the Good Shepherd, newspaper for the Archdiocese of Abuja, Nigeria,

peering out the window at the treetops of a vast and verdant rainforest.

Bologo, who also is pastor of Holy Rosary Catholic Church, and

the rest of the reporters and producers participating in the UCIP

Summer University program checked to see if they had rosaries,

just in case. Seconds later and several hundred feet farther down,

the faces of passengers seemed to ask a common question: Is this

flight worth the risk?

The answer slowly came into view as the plane bounced through

an air pocket and entered the thin misty clouds over the green

interior of Guyana.

Here flows the clear water and creamy froth of what government

officials and businesspeople hope will be the future draw to this

Caribbean state located on South America’s northeastern coast:

Kaieteur Falls.

Most people have never heard of it.

It is one of the highest single-drop waterfalls in the world.

At 741 feet,

it is five times the height of Niagara Falls.

Guyanese and foreign investors have faith that eco-tourism, the

business of visiting wonders like Kaieteur Falls will begin to

improve the economy of the second-poorest nation in the Western

Hemisphere.

The flight out of Guyana’s capital of Georgetown to Annai revealed

a natural beauty hidden away from city residents. From the cattle

en route to fresh water to the bronze-skinned women and men making

cassava bread, this Guyana was a far cry from urban Georgetown.

Out here, Catholics and Anglicans send their children to rural

schools funded by United Nations programs. As Bologo and others

learned, it’s not unusual to learn one’s ABCs from a chalkboard

at rest below a tree rooted along a savannah. Parents don’t have

the option of sending their children to classrooms where religion

is part of the curricula.

Unlike Trinidad and Tobago, where denominational schools—including

Catholic and Anglican—make up 357 of the country’s 481 schools,

in Guyana Catholic schools were a thing of the past until as recently

as 1998.

Shortly after Guyana officially gained its independence from Britain

in 1966, the nation turned socialist and ended the historic presence

of Catholic and other religious schools. Buildings that once housed

religious orders and their schools are now occupied by businesses

and various government agencies.

It was a change that also affected Guyana’s press: For nearly

four decades, the harsher aspects of that truth have been difficult

to put into print.

No one knows that better than the journalists who have given their

blood, sweat and tears to maintain the voice

of The Catholic Standard, the nation’s only Catholic newspaper.

Setting the Standard

Jesuit Father Andrew Morrison knew he was as good as dead.

The men with guns, those loyal to the Guyanese government, were

fed up with the objective reporting and biting editorials published

by Morrison, editor of The Catholic Standard, the official newspaper

of the Diocese of Georgetown. Beyond the paper, Morrison, a white

Catholic priest, was involved in the edges of the political struggle

for democracy in the country.

So it was no surprise when late one night the men with guns blew

a hole through the head of a white Jesuit priest on the streets

of Georgetown.

The surprise was the victim wasn’t the Catholic Standard editor.

Morrison’s story is documented in the book “Justice: The Struggle

for Democracy in Guyana 1952-1992.” Its cover shows a photo of

Jesuit Father Berbard Darke being chased across the road by a

religious cult member. Later that day he was found beaten and

stabbed. That pursuit was believed to have come from an order

from a leading government official.

Established in 1905, The Catholic Standard’s reputation for telling

the truth led to its inclusion in the microfiche files of the

United States Library of Congress as a record of what happen during

Guyana’s decades of political turmoil.

Few Catholic papers in the United States own their own presses.

At The Catholic Standard presses run hot each week in the ground-level

floor of the modest two-level flat housing its offices.

Under Afro-Guyanese editor Colin Smith, The Catholic Standard

continues to question problems in the country’s electoral system

in addition to announcing priest appointments to the diocese’s

19 parishes. It’s a matter of keeping a record of faith and life,

unedited by political or secular influences.

The miracle of Marian Academy

There is something familiar with the urban poverty of Georgetown.

The depressed areas aren’t much different from those on the West

Side of Chicago.

These places are neither all encompassing nor reflective of the

entire city, yet can’t be ignored. They are evidence of a condition

further magnified by the lack of educational choices offered to

children of the city.

In Chicago and other U.S. metropolitan areas, Catholic schools

offer an alternative to government-funded public schools for students

regardless of their religious identity. In Guyana, there are government

schools and more government schools.

That wasn’t always the case.

Middle-aged citizens can remember attending single-sex Catholic

schools in Georgetown. Those schools disappeared under a series

of Marxist, socialist and communist systems and government claims

to land held by the diocese and religious orders.

Ursuline Sister Jacqueline De Silva remembered the day in 1976

when government forces took over their Catholic school, sending

the sisters into their residence in order to keep the convent.

The irony of Guyana is that this nation is best known by the actions

of a religious figure.

In 1978, the Rev. Jim Jones, a religious cult leader came to Guyana,

to start a commune called Jonestown. Under the direction of Jones,

over 900 of his followers consumed cyanide-laced Kool-Aid, committing

the largest mass-suicide in history.

Whether talking to government officials in Georgetown or Rupurundi

near Annai, there is a burning desire to erase the memory of Jonestown.

Gerry Gouveia, president of the Tourism and Hospitality Association

of Guyana, said, “Image can be everything.”

Other images remain, like statues of Mary at St. Rose High School.

Founded in 1847 by Irish Ursuline sisters, St. Rose was the first

secondary school for girls in Guyana. In the relative absence

of denominational schools, religious orders have attempted to

fill the void.

Ursuline Sister Claudette Jones works with school drop-outs and

other “at-risk” teens through a program called Hope in Youth.

The program is modeled after the SERVOL program started by Father

Gerry Pantin in Trinidad.

Some of the teens she encounters, Jones said, cannot read, but

are able to get by understanding basic words and traffic signals.

They also face numerous personal and societal hurdles.

Yet, in spite of financial and other obstacles, De Silva believed

the time was right to get back to the basics of Catholic education.

De Silva’s goal is to move students beyond functional literacy

by starting Marian Academy, the city’s only Catholic school in

decades.

What started on a modest plot of land near an outdoor cricket

field has grown to include the construction of an additional complex

twice its size across the road.

Today, students both Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese, girls and

boys are once again linked to the rich history of learning through

the work of Ursuline sisters.

With the arrival of Marian Academy, the dream of Catholic education

has once again taken flight in Guyana.

Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview

Classifieds | About Us | Write Us | Subscribe | Advertise

Archive | Catholic Sites | New World Publications | Católico | Directory | Site Map

|

|