|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Campaign gives voice, resources to those in need

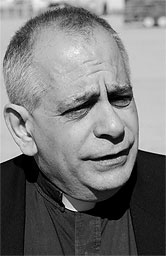

Father Robert J. Vitillo is a priest of the Diocese of Paterson, N.J., but with his love of Italian cooking, he claims Rome as his hometown. After spending 10 years in Rome working for Caritas Internationalis, he returned to the United States, and in 1997 took on the job of leading the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ domestic anti-poverty effort. Parishioners in the Archdiocese of Chicago perennially give more to the campaign than those of any other diocese in the country. Vitillo talked with Catholic New World staff writer Michelle Martin on a bus trip across New Mexico during the campaign’s “Breaking the Cycle of Poverty” tour of anti-poverty projects in the nation’s poorest state. For the story, see Pages 16-17.

The Catholic New World: What are the goals of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development? Father Robert J. Vitillo: Basically we have two goals. One is to support community-based self-help projects that are created and led by poor people themselves to bring about change in their own communities so that they can overcome poverty. The second goal is to educate Catholics and others about the root causes of poverty in our country, and especially to help Catholics to link the practice of their faith with action in their communities to overcome poverty.

TCNW: Why is it important that the projects be led by poor people themselves? FRJV: Well, the whole idea when the campaign was started back in the early 1970s, (there was) an awareness of the growing gap between the rich and the poor, and the bishops were very concerned about the social changes that were going on in our country. They already knew that the Catholic Church was very much involved in doing things for poor people, through Catholic Charities and Catholic education and Catholic health care, but they realized that wasn’t enough. So when they started this new effort. they wanted to help the poor people themselves develop political and economic power in the community. The bishops realized that you couldn’t help them do that by telling them what to do. It was up to poor people themselves to find the solutions to poverty, with the help of others.

TCNW: Is part of that a measure of respect? FRJV: Absolutely. If you really believe that everyone has a unique dignity given by God, then you really show respect for that dignity. That’s the whole idea of this: That when people who are living in poverty are shown respect, they feel better and they can work to overcome a lot of things on their own.

TCNW: The other part is education. Is it difficult to make people who aren’t poor see those who are? FRJV: I think it is. When we first started the “poverty pulse” as we call it, we discovered that less than 3 percent of the population identified poverty as a major social problem. ... Americans are much more concerned about some of the effects of poverty, like violence in the streets, like drug use, like poor education, but they don’t always make the connection that a lot of the root cause of that is poverty, and the endless cycle of poverty. Even beyond making people aware of that, you have to help them overcome the myths, like, “If only people pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, they wouldn’t be poor anymore.” Most poor people work very, very hard, but it’s really kind of an endless cycle unless they have the help to really get started to make structural changes.

TCNW: What are some of your success stories? FRJV: The real success stories are the projects, the organizations we’re supporting. I don’t say that it’s the individuals, although they’re the people who have benefited. I really think it’s the groups, because ... no longer was it poor Mrs. X who was going to ask the mayor or council to do something. It was a more substantial group of the community that called attention to the injustice that they might be living with.

TCNW: How do you compare poverty in the United States with poverty internationally? FRJV: I don’t think you can use only an economic or a monetary scale. Obviously, poor people in the United States make more money than poor people in other countries. But you have to compare that with what it costs to live in the United States, and you also have to look at some of the psychosocial factors of poverty in the United States. In many other countries, people certainly suffer because they are poor, but they also have certain resources within the basic community. They usually live closer to their families, (and) they have the support of the wider community because of the environment they’re living in. It doesn’t take away the pain of living in poverty, but it does give them a wider support group than many people in the United States have. There’s also a bigger sense of sharing among poor people in many other countries, so they sort of supply the needs of each other, even though they don’t have much. That doesn’t seem to happen as much within the United States. TCNW: Even with all the successes, the gap between rich and poor has grown wider. Do you think that can be remedied by what, after all, in the grand scheme of things, are small projects? FRJV: I don’t think it can be remedied that way on the grand scale, but I do think we make a difference in individuals’ lives and in communities’ lives. I think that, plus a lot of conversion and change in mentality, and a greater sense of solidarity, can make a change on a grand scale. I don’t see that happening yet. But we’re people of faith, so we have to keep believing. TCNW: Why should we care? FRJV: To me, as a person of faith, I really do believe we’re all family. As St. Paul says, if one member of the body hurts, then we all hurt. Even on the macro level, when we’re using third-grade test scores to plan prison beds in California, we have to understand that if we’re not helping people who are poor get good education, then we’re going to pay the consequences in society. You can also say, what does it matter about a colonia in New Mexico when I live in Chicago? There too, I can say it’s very, very evident to me as I travel the country that the colonia is coming to the entire culture. There are pockets of poor Latinos arriving all over the country, in places that never expected Latinos. I did a talk in Crookston, Minn., last summer, and I found a whole group of Latinos. … And we need them too, to do the work that so many others who have been here longer won’t do or don’t want to do. To me, especially with the Latinos—maybe I say that because I feel I share some Mediterranean blood with them—the culture, the values, the family values, there are so many things we desperately need, and they can help us so much by becoming part of our culture.

Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview |

||||||||||