|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Clergy sex abuse was biggest religious news of the year

By Jerry Filteau The second year of Christianity’s third millennium will go down in religious history as the year the clergy sexual abuse crisis rocked the U.S. Catholic Church to its foundations. By year’s end it was widely regarded as the gravest crisis ever faced by the Catholic Church in the United States, capped with the resignation of Boston’s Cardinal Law. (See story, Page 1.) It also was a year of continued violence in the Holy Land, famine and a catastrophic AIDS pandemic in Africa, a global U.S. war against terrorism and threats of war against Iraq. It was a year of further travels by an aging Pope John Paul II, including a World Youth Day visit to Toronto in July. It was a year of new church controversies over liturgy, homosexuality in the priesthood and ordination of women. Religious discrimination, Muslim-Christian conflict and Catholic-Jewish relations often made the news. But overshadowing other religious news throughout the year were the ongoing dramas of sex-abuse debates, lawsuits and removal of priests.

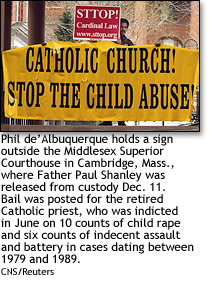

In January defrocked Boston priest and serial child abuser John Geoghan was convicted of indecent assault on a 10-year-old boy—out of hundreds of allegations, almost the only case that was not barred from criminal trial by the statute of limitations. And the Boston Globe got a court-ordered release of archdiocesan files on Geoghan, giving a shocked public an unvarnished inside view of archdiocesan dysfunctions in dealing with abusive priests. The released papers quickly led to the escalation of the Boston scandal into a national church crisis—played out repeatedly in other dioceses as newspapers across the country began digging deeper into how the local diocese had handled such cases over the past 20, 30 or 40 years. By April the U.S. cardinals were called to a special summit at the Vatican to chart a course of action, and the world heard Pope John Paul II’s statement that “there is no room in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young.” Encouraged by the changed atmosphere across the country, hundreds of clergy abuse victims who had suffered silently for years or decades came forward and told their stories. By June, when the U.S. bishops met in Dallas to debate a mandatory national policy to oust perpetrators and protect children, more than 200 priests had been pulled from ministry across the country and the story was making daily headlines. By December, the nearly 140 lawsuits the Boston Archdiocese had settled with Geoghan victims paled before the several hundred others filed on behalf of alleged victims of other Boston priests. The archdiocese took the first steps toward filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Also in December: - The bishops of California warned their people to expect hundreds of clergy sex abuse lawsuits across the state in 2003 because of a new law taking effect Jan. 1 that would waive the statute of limitations on such suits for a year. - The Diocese of Manchester, N.H., entered a settlement with the state attorney general, avoiding unprecedented criminal charges in return for admitting it probably could be convicted of child endangerment. As part of the settlement, the diocese agreed to the public release of thousands of pages of personnel files detailing how the diocese dealt with decades of accusations of sexual abuse against a number of its priests. In June, the U.S. bishops adopted a “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People” and approved a set of legislative norms to enforce implementation in all dioceses. They established a National Review Board, headed by Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, to monitor compliance, study the causes of the crisis and recommend further church steps to protect children. They formed a national Office for Child and Youth Protection and in November appointed Kathleen L. McChesney, a top FBI official, to head the office. Bishop Wilton D. Gregory of Belleville, Ill., was widely credited by church observers with engineering Vatican consent to the idea of special national legislation to deal with the crisis, overriding the usual autonomy of each bishop in his own diocese in such matters. At the June meeting he squarely confronted the bishops with their own responsibility, saying, “The crisis, in truth, is about a profound loss of confidence by the faithful in our leadership as shepherds, because of our failures in addressing the crime of the sexual abuse of children and young people by priests.” In October Cardinal George and a small commission of U.S. bishops and top Vatican officials revised the June legislative norms to put them into greater conformity with general church law, introducing criminal trials by church tribunals as the ordinary way to permanently remove priests who have sexually abused children. In their final form, the norms explicitly stated that religious priests were also subject to the norms. Cardinal Law was not the only U.S. prelate to face controversy for past handling of abusive priests. Among those who came under the heaviest media criticism were Cardinals Edward M. Egan of New York and Roger M. Mahony of Los Angeles, but numerous other bishops and archbishops found themselves forced to defend past actions. The crisis also led to the resignation of four U.S. bishops. - Bishop Anthony J. O’Connell of Palm Beach, Fla., resigned in March after admitting inappropriate sexual contact with a high school seminarian many years earlier. - Archbishop Rembert G. Weakland of Milwaukee had already submitted his resignation on his 75th birthday when it was revealed May 23 that in 1998 he had reached a $450,000 settlement over sexual misconduct in 1979 with an adult male. The next day the pope accepted his resignation. - New York Auxiliary Bishop James F. McCarthy turned in his resignation in June after admitting to affairs with several women. - Bishop J. Kendrick Williams of Lexington, Ky., facing three accusations of sexual abuse, denied the claims but resigned in June. The sex abuse crisis fed new debates about what qualifications should be required of a candidate to be accepted for ordination. The charter the bishops adopted called for Vatican-sponsored visits to all U.S. seminaries, with a focus on the quality of their programs of formation for celibate chastity. There were also revived arguments over mandatory celibacy and the admission of women or married men to the priesthood. But one question—the admission of homosexually oriented men to ordination—was debated with special vigor. In March Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro-Valls said people with homosexual inclinations “just cannot be ordained.” In September a priest working in the Vatican Congregation for Bishops wrote an article in America magazine arguing that homosexuals should not be ordained. Although he wrote it on his own, many veteran church observers regarded it as a trial balloon signaling Vatican thinking on the topic. The following month it was learned that the Vatican’s education congregation, which oversees seminaries worldwide, was circulating a draft document that said homosexually oriented men should not be admitted to seminaries. In December the worship congregation, which oversees administration of the sacraments, published a response it had given six months earlier to a bishop in which it said ordination of homosexuals is “absolutely inadvisable and imprudent.” In the U.S. war on terrorism, President Bush’s threats to attack Iraq drew criticism from religious leaders around the world, including the U.S. bishops, who warned that they could see no justification for a pre-emptive, unilateral attack. When Iraq accepted the U.N. demand to revive weapons inspections, Pope John Paul welcomed it as a possible path away from the threat of a war that would throw the whole Middle East into turmoil. Violence was a daily fact of life in the Holy Land as scores of Palestinian suicide bombers struck out at Israelis and Israeli soldiers retaliated for each new incident. The terror moved abroad in November as 16 were killed in a suicide bombing at a favorite Israeli resort in Kenya. Even as the world community seemed finally on a path to relieve the crushing external debt burdens of impoverished nations in sub-Saharan Africa, the region’s AIDS pandemic brought harsh new social and economic problems. An estimated 28 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were suffering from AIDS in 2002, and the disease attacked mainly young and middle-age adults who should have formed the region’s most productive work force. Drought, compounded by poverty and the AIDS health care crisis, led to the start of a new famine in Africa that could surpass the famine of the mid-1980s. A coalition of 15 U.S. aid organizations, meeting at Catholic Relief Services headquarters in early December, warned that 38 million Africans risk starvation unless the international community mobilizes quickly. Muslim-Christian conflicts continued in parts of Africa and Asia. In June a Sudanese government plane dropped four bombs on a bishop’s residence and 12 bombs on a Catholic mission where 500 children attend school. Christian-Muslim tensions in Nigeria flared into November riots that left more than 200 dead. In Pakistan, Archbishop Lawrence Saldanha of Lahore in early September said the past year was unprecedented for the number of extremist Muslim attacks and killings of Christians. Three weeks later two gunmen massacred six Catholics and a Protestant in an attack on an ecumenical justice center. A U.S. Catholic-Jewish consultation issued a statement in which Catholic participants affirmed that God remains faithful to his saving covenant with the Jewish people and said Christians should not engage in campaigns targeting Jews for conversion. Some Catholics took issue, calling the statement a denial of the church’s mission. Pope John Paul II—who turned 82 in May—remained a major figure on the world scene despite physical ailments that caused him to reduce his travels and limit his public appearances. The aging pontiff traveled to Azerbaijan and Bulgaria in May, calling for religious tolerance and Catholic-Orthodox reconciliation. In summer he traveled to Canada, Guatemala and Mexico. In Toronto he celebrated a World Youth Day Mass before an estimated crowd of 800,000. In Guatemala he canonized St. Pedro de San Jose Betancur, a 17th-century missionary. In Mexico he canonized St. Juan Diego, the 16th-century Mexican peasant whose visions of Mary marked the start of devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe. The pope’s Aug. 16-19 visit to Poland was his 98th trip outside Italy and his ninth return to his native land since he became pope. In October he marked the 24th anniversary of his papacy by proclaiming a “year of the rosary” and suggesting an optional new five mysteries of the rosary, called “mysteries of light” and focusing on events in Christ’s public ministry. On Nov. 14 he made a historic first papal visit to the Italian Parliament, delivering a 50-minute speech on a wide range of challenges facing Italy, from its treatment of the poor and immigrants to its dangerously low birth rate. In February the Vatican called for a worldwide ban on human cloning. The issue divided U.S. legislators, who could not agree whether to ban all human embryonic cloning or to permit it for medical research. In June, six European Catholic women and an American, former Ohio first lady Dagmar Celeste, claimed to have been ordained priests in Europe by an excommunicated Argentine priest who claimed to have been ordained a bishop by another excommunicated priest who was ordained a bishop. The Vatican called the women’s ordinations invalid and excommunicated the seven. At their November meeting the U.S. bishops approved a joint letter with the Mexican bishops on migration, an updated plan for Hispanic ministry, approval of liturgical texts, new fund-raising norms and a new handbook on diocesan financial administration, record-keeping and reporting. Reserve funds of many dioceses took a severe hit from the broad decline in the stock market. In June the Boston Archdiocese laid off personnel and slashed its annual budget from $24 million to $16 million. In September the Los Angeles Archdiocese closed several offices and laid off dozens of employees to eliminate a $4.3 million budget deficit, but attributed the belt-tightening to investment losses, not the sex abuse crisis or the costs of the new $189 million cathedral. When the Miami Archdiocese laid off 10 percent of the staff at its pastoral center, it cited a $31 million loss in its investment portfolio as the reason. Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview |

||