|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

| U.S. bishops expected to OK new abuse norms

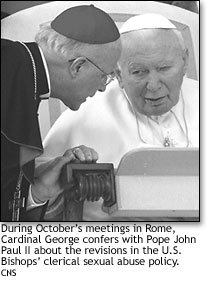

By Michelle Martin As U.S. Catholic bishops prepared to gather in Washington D.C., Cardinal George said he expects the bishops to approve revisions to documents aimed at protecting children and teenagers from sexual abuse by priests. The revised Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People and the norms that go with it were released Nov. 4, about a week after Cardinal George and three other U.S. bishops worked out the changes with four Curia officials at the Vatican. The U.S. Conference of Catholic bishops will discuss and vote on the changes at its Nov. 11-14 meeting. Cardinal George said the revisions leave intact the main goal of protecting children, and in some cases strengthen the hands of bishops when it comes to dealing with cases of clerical sexual abuse. But perhaps the biggest change is the requirement for an accused priest to be tried in a canonical court before he can be removed permanently from ministry or the priesthood. “What they add is the possibility of using a non-administrative procedure—a judicial procedure, a trial,” the cardinal said, to come to an understanding of what happened and to protect the rights of the accused cleric as well as the victim. “Under canon law, if you want to impose a permanent penalty, there has to be a judicial method.” Cardinal George writes about the revisions in his column on Page 3 of this issue of The Catholic New World. The original charter and norms approved at the June bishops’ meeting in Dallas did not call for church trials because, under canon law, the statute of limitations says accusations must be made by the time a child sexual abuse victim turns 28. The bishops wanted the freedom to remove an offending priest from ministry, and even from the priesthood, no matter how long ago the abuse occurred. The revised norms say U.S. bishops can apply to the Vatican to have the statute of limitations waived on a case-by-case basis. The change fixes a problem that many critics pointed out soon after the Dallas norms were published and sent to the Vatican for consideration. “I said at the time that there were elements in the documents that were self-contradictory, but we had to approve them because we knew what we had to do,” Cardinal George said. Father Patrick R. Lagges, the archdiocese’s director of canonical services, said he has never actually seen a canon law trial held to determine a penalty such as removing a man from the priesthood, because church procedures allowed bishops to take such cases to trial only when “the scandal could not be repaired, justice could not be restored and the offender could not be reformed in any other way.” “Now, because the magnitude of the scandal is so great, the injury is so tremendous, and, from all we’ve learned in the past 15 to 18 years, the offender cannot be reformed, we are going to start seeing these trials,” he said. Some of the first could involve five priests of the Archdiocese of Chicago who have said they intend to appeal their removals. The five are: Fathers John Callicott, Daniel Buck, John Keehan, James Ray and Thomas Swade. They are among 14 archdiocesan priests barred from ministry since March. No one should imagine dramatic confrontations like those on “Law & Order,” Lagges said. When a fitness review board determines that there is reasonable suspicion that a cleric has committed some act of sexual abuse—defined in the revised norms as conduct with a minor that “qualifies as an external, objectively grave violation of the Sixth Commandment”—the bishop is to immediately report it to the Vatican’s Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, as required by the Vatican since 2001, and, if necessary, ask for a waiver from the statute of limitations. “They’re saying, ‘We want to make sure you do something about this,’” Lagges said, explaining that, if the revised norms are approved, the congregation would normally send the case back to the United States for a canonical trial. Under the revised norms, the accused priest would be barred from public ministry from the time the bishop decides the accusations are credible throughout the proceedings, Lagges said. The makeup of the tribunal that conducts such a trial remains open for debate, Lagges said. He expects the bishops to consider creating some kind of regional tribunal, to make it less likely that the judges will know the accused and to create more of a sense of distance and objectivity. Whoever puts the tribunal together, it will consist of three or five canon lawyers, not necessarily priests. A “Promoter of Justice” will take the role of the prosecuting attorney, formally requesting a trial and the dismissal of the accused from the clerical state. The tribunal will then advise the accused of the charges, suggest he appoint counsel, and begin gathering evidence by collecting documents, possibly including counseling records from the victim and accused, and using auditors—generally lay people—to go out and conduct interviews with the people involved and any witnesses. Once they have gathered evidence, the tribunal members will share it with the promoter of justice and the accused and his counsel, giving both sides a chance to respond. They can also share it with outside experts, called assessors, who might be able to offer guidance as to whether the case fits the pattern of sexual abuse, Lagges said. Each member of the tribunal reaches their own opinion, they meet to discuss them, and they issue a joint decision, Lagges said. Unlike the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard most Americans are familiar with, the tribunal must have “moral certitude” that it has reached the correct decision. “Of course, the more time since the alleged offense took place, the harder it is to reach moral certitude,” Lagges said. “But it’s the same standard we have for determining the nullity of a marriage, which can be difficult if the marriage lasted 25 or 30 years. That’s why you have so many people involved in the trial. You have all these people looking at the same thing.” In cases where there is a split in opinion, or there is some evidence, but not enough to reach “moral certitude” and dismiss a man from the priesthood, it would be up to the bishop to keep the priest from public ministry. “The bishop has a responsibility to protect children and young people, and he’s not going to do anything to jeopardize that,” Lagges said. However, members of victims’ advocate groups have criticized the requirement for a trial because, they say, it leaves open the possibility that a priest who has sexually abused children could be cleared and returned to ministry. Lagges said he understands that people who have been hurt by a cleric, and then often by the church itself, might not be satisfied by any church-run process. “It’s very natural that they would be suspicious of that same church coming back and saying, ‘Trust us,’” he said. Perhaps for that reason, victim advocates have also called into question a revision that stops short of requiring bishops to report all allegations to civil authorities. The new wording requires them only to comply with civil laws, which do not require such reporting in all states, and to encourage victims to report their allegations to civil authorities themselves. Jim Dwyer, an archdiocesan spokesman, said allegations of sexual abuse are “always reported” to civil authorities, and have been “since 1992. But most people have praised revisions which make clear that the norms apply to religious as well as diocesan priests in the United States, and that prohibit a bishop from transferring a priest with a history of abuse to another diocese for ministry. The Vatican had called for revisions to the original norms passed in Dallas because of concerns that they conflicted with canon law. For the norms to become binding on all U.S. diocese, the Vatican must give them its “recognitio,” or approval. In a mid-October letter, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, head of the Congregation for Bishops, suggested a mixed commission of U.S. and Vatican bishops work together to find mutually acceptable wording. After two days of meeting with them at the end of October, Cardinal George said the Vatican officials understand the gravity of the situation. “We found them very helpful,” said Cardinal George, who was accompanied by Archbishop William J. Levada of San Francisco, Rockford Bishop Thomas G. Doran and Bridgeport, Conn., Bishop William E. Lori. “They understand the horror of this, and they are very concerned that this scandal be faced up to.” The Vatican officials who participated in the meeting were Cardinal Dario Castrillon Hoyos, prefect of the Congregation for Clergy; Archbishop Julian Herranz, president of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts; Archbishop Tarcisio Bertone, secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith; and Archbishop Francesco Monterisi, secretary of the Congregation for Bishops. If the U.S. bishops approve the revised norms in November as expected, they will go back to the Vatican for approval. In the meantime, most U.S. dioceses have already started implementing them.

Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview |

||||

|

||||