|

|

Future docs plunge into serving poor

By Michelle Martin

Staff writer

Junior will always stand out among Sarah Carreon’s memories of her 10 days in Haiti.

Junior is a bright, happy 8-year-old—“He’s just beautiful,” Carreon said—despite a disfiguring tumor on his face that has made it difficult for him to eat and breathe and is now eating into the bones of his skull. Junior is a bright, happy 8-year-old—“He’s just beautiful,” Carreon said—despite a disfiguring tumor on his face that has made it difficult for him to eat and breathe and is now eating into the bones of his skull.

Carreon and nine other students from Loyola University’s Stritch School of Medicine met Junior at St. Boniface Hospital in Fond des Blanc, about 60 miles outside Port au Prince where they were assisting two U.S. doctors. They traveled as part of a campus-ministry sponsored immersion program designed to connect medical students with service opportunities in the developing world.

“He’s an incredible person,” Carreon said about Junior. “I can speak for the group. He gave all of us hope.”

Now the students and the doctors on the trip have mounted a letter-writing campaign, trying to get permission and funding to bring Junior to Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood for treatment, and Carreon and several classmates are looking forward to continuing service once they get their medical degrees.

That’s one of the outcomes Sister Brenda Eagan hopes for when she organizes the 10-day to three-week experiences for students just finishing their first year of medical education. This year, nearly 70 of the 130 members of the class of 2005 opted to spend time in poor communities in Haiti, Guatemala, Belize and Ecuador, sharing their admittedly limited medical knowledge and a bit of themselves.

“What I want the students to get out of it is a deeper sense of their responsibility, to humanity and to themselves,” said Eagan.

The program started nine years ago when three students asked the campus ministry office for help finding a service opportunity, said Eagan, a member of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The original three were linked with the Working Boys Center in Quito, Ecuador—still one of the program’s sites. Eagan has found other places mostly by working with established medical clinics or hospitals tied to religious congregations, she said.

Participating students help with an auction fundraiser that paid for most of the program, and each paid $500 to participate.

The students come from many religious backgrounds—some from no religious background at all, Eagan said. But spending time living with people of another culture and serving them helps everyone involved.

“What I would hope the people get out of it is that we are interested in their lives and we are in solidarity with them,” Eagan said. “They are seen and they are heard and they are valued. The way we honor one another in the human community is by showing up. … Because these are medically oriented people, it made sense to do it through medicine.”

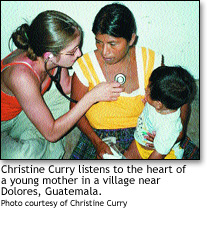

Christine Curry knew that her two-weeks in rural Guatemala would mean mosquito netting, days without running water or electricity, and people suffering from parasitic illnesses.

What Curry, 23, from Downers Grove, didn’t understand was how much fun it would be to spend 20 minutes teaching a group of Guatemalan children how to throw a Frisbee—using nothing but body language and facial expressions.

“In the villages, a lot of the people were descendants of the Mayans and spoke Mayan languages,” she said. “Some didn’t speak a word of Spanish, so we had to communicate basically by sign language. But we worked so hard at it, sometimes we ended up building more of a rapport that way.”

For Curry, medical knowledge was one of the main attractions.

“I wanted to see how medicine was practiced without all the bells and whistles of a modern American hospital,” she said.

The nine students and two doctors on her trip used a convent in Dolores, Guatemala, as their base. The students then divided into two groups, one with each doctor, and made one- or two-day trips to villages in the countryside, providing simple medical care and exams in schools and churches. Those trips provided the best opportunity for reflection, Curry said, since there wasn’t a lot to do once the sun set.

In the villages, dozens of people would be lined up even before the students unloaded the donated medical supplies off trucks. Many had worms or dysentery, and some seemed to be suffering from malaria. Those that had malarial symptoms had to be referred to another medical clinic—the teams had no microscopes to provide a definite diagnosis, and generally no place to plug a microscope in even if they had one.

In Haiti, Carreon helped take medical histories and give physical exams. She got a quick education in various infectious diseases, from parasites to bacterial infections to tuberculosis.

Amy Hagan, 23, of Tinley Park, assisted in surgery, helped deliver babies and conducted physical exams as part of another team in Haiti. She was one of nine students sent to Sacred Heart Hospital in Milot, who got three weeks of contact with patients they would not get until their last year of medical school in the United States.

While she and eight fellow students were “treated like royalty” at the sisters’ residence where they stayed, she also had her first experience of everything being a little unfamiliar, from the food to the lack of reliable hot water. She admitted she had a hard time facing her dinner, just hours after seeing the goat that made up the main course tethered in the back yard.

Carreon also encountered “lots of goat” in her meals, and some guilt, as well, because the American students were fed plentifully and often in an area where many people suffer from malnutrition.

“If I had to use one word to describe the people, they were very hospitable and gracious, she said. “They cooked this food for us, and they were proud of it. Even though we felt a little guilty, we were going to eat it, and be appreciative.”

The students who went all came away with a new appreciation of how people who by American standards are destitute can be very happy and appreciate what they do have.

Curry said she went to Guatemala expecting to help “those poor people.”

“What I found was that they really had it together,” she said. “They had really strong social structures in the villages we visited. They really helped each other. And when you’re in someone’s home, you really can’t complain that it’s hot and dirty and say it’s terrible, because you’d basically be saying their way of life sucks. And it doesn’t. But it is different.”

Top

Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview

Classifieds | About Us | Write Us | Subscribe | Advertise

Archive | Catholic Sites | New World Publications | Católico | Directory | Site Map

|