|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

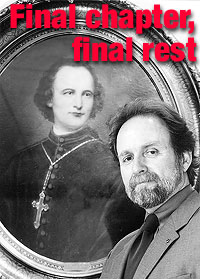

Archdiocesan archivist John Treanor with a portrait of Bishop

James Duggan Catholic New World/David V. Kamba |

|

Chicago’s fourth bishop ‘home’ after 102 years

By John J. Treanor

SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

Bishop James Duggan has come home. On March 29, in a private ceremony,

the mortal remains of Chicago’s fourth bishop were solemnly and

ceremoniously moved from Calvary Cemetery in Evanston and placed

in the Bishop’s Mausoleum at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside.

Bishop Duggan died March 27, 1899, in St. Louis.

While the moving of a body from one burial site to another is

not all that uncommon, the circumstances surrounding the episcopacy,

death and burial of Bishop Duggan provide an interesting story.

His life and times have all the ingredients of a Greek tragedy:

A young life full of promise, grace and opportunity; insidious,

progressive psychological problems; intrigue and a steep fall

from prominence all add to this effort to restore dignity to the

most tragic figure in archdiocesan history.

People often say historians commonly interpret the “historical

facts” as they see fit. While it is true that statistical data

can be “interpreted,” most historians would argue that facts such

as in this case, Bishop Duggan’s birth, death installation and

removal are indisputable reference points.

What historians do argue over, however, is why these historical

events occurred. As more records become available over time, historians

bring new insights as well as their own perceptions, politics

and prejudices to influence their interpretation of the event.

So why did it take 102 years after his death to move Bishop Duggan’s

mortal remains into the Bishop’s Mausoleum where rest most of

the bishops who have lead the Church of Chicago? The Bishop’s

Mausoleum was completed in 1912 and the remains of Bishop William

Quarter (1844-1848) and Archbishop Patrick A. Feehan (1880-1902)

were placed there. Only Bishop Duggan remained elsewhere. Why?

To answer that question we must understand the life and times

of Bishop James Duggan, whose episcopacy lasted from 1859-1869.

The son of a clothier, he was born in Maynooth, Ireland, and grew

up virtually in the shadow of the famous Irish seminary that bears

that town’s name. He came to the United States in 1842 at the

request of Archbishop Peter Kenrick of St. Louis, to finish his

seminary training at St. Vincent’s Seminary in Cape Girardeau,

Mo. He was ordained a priest in 1847 at the age of 22.

Contemporary accounts describe him as a handsome man with a gift

for languages and great skill in oration. He left a crowded Ireland,

then on the brink of the Great Famine, to answer the urgent call

for priests in the young U.S. Catholic church. His intellect and

eloquence distinguished him and in 1854 he was appointed vicar

general. Indeed, that same year while only five years a priest,

Archbishop Kenrick appointed him to administer the Chicago Diocese

when Bishop James O. Van de Velde (1849-1853), abruptly resigned

in 1853.

He was 31 when Archbishop Kenrick consecrated him bishop of the

titular see of Gabala and coadjutor bishop of St. Louis. He was

again asked to administer the Diocese of Chicago in 1858 when

Bishop Anthony O’Regan, the third bishop of Chicago, resigned.

On Jan. 21, 1859, Bishop Duggan was appointed the fourth bishop

of Chicago. He was only 34.

Ten years later, on April 14, 1869, Bishop Duggan was removed

from office and spent the next 29 years living in a sanatorium

run by the Sisters of Charity in St. Louis. He died there on March

27, 1899.

Little is known of Bishop Duggan’s treatment in the sanatorium.

He was described in one historical account as “hopelessly insane.”

The diagnosis and treatment of mental illness has changed dramatically

since the mid-19th century.

Indeed, the observation of “hopelessly insane” is not a valid

clinical diagnosis. What illness did he suffer from and why was

he institutionalized? With the lack of medical records, it is

almost impossible to say with any degree of certainty what ailed

Bishop Duggan.

However, if we carefully examine the times in which he lived and

correspondence from those who knew him it may be possible to make

some assumptions.

His tenure as bishop of Chicago was fraught with challenges and

turmoil. Two years before his appointment, the financial panic

of 1857 caused severe fiscal hardship that clearly impacted the

nation’s economy for several years. Unemployment was high and

it is a fair assumption that there was less money available for

church needs. Keep in mind that during this period Chicago was

indeed the “Second City,” in that St. Louis was the Midwest’s

larger and more influential metropolis.

In addition, both his predecessors had resigned, so Chicago was

not a prime choice for anyone with episcopal ambitions. In reality

the juvenile church of Chicago lacked any real leadership in the

years following the death of Bishop Quarter.

Tensions between Irish and German Catholics provided a contentious

climate upon Duggan’s arrival. German Catholics were greatly disappointed

that a German-speaking bishop was not appointed.

Whether it was an attempt to show his anti-Irish detractors his

mettle or his dogmatic adherence to papal dictates against secret

societies, Bishop Duggan took a harsh stand against the Fenian

Brotherhood. He enjoined his priests to deny sacraments to anyone

with known ties to this secret society dedicated to freeing Ireland

of British rule by physical force. This angered many of his Irish-born

priests.

Three years into his tenure, the nation was plunged into the horrors

of the Civil War, an event that shredded social fabric.

The University of St. Mary of the Lake, the first chartered university

in Illinois, with its attached seminary was a victim of the conflict.

The university saw a precipitous decline in enrollment as well

as financial support. Some of Bishop Duggan’s clergy felt that

he did not do enough to support the university.

Signs of stress and erratic behavior first appeared after his

return from the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore (a collegial

meeting of American bishops) in 1866. He was described by at least

one colleague as having a “delicate disposition” and “spinal”

problems. His behavior became erratic and his friends started

to notice changes in his mood and temperament.

Citing various ailments, Bishop Duggan traveled abroad for an

extended period, to seek relaxation and cure. During his absence

several priests, concerned about the bishop’s behavior and stability

petitioned Rome to look into the matter. Upon his return, he closed

the seminary and dismissed four priests, some of whom had been

his closest advisors.

It was now clear to Rome that the situation in Chicago needed

to be addressed.

From our vantage point, over 130 years later, we can see Bishop

Duggan was placed in a difficult position at a very young age.

The stress and pressures of the job were undeniably enormous.

They evidently affected his physical and mental health and he

was no longer able to distinguish his friends from his enemies.

His judgments were erratic and he sought escape from his obligations

and responsibilities.

In today’s society we have a greater understanding of the symptoms

of job-related stress. We exercise, go on vacation, seek counseling

and, if necessary, take medication. Too often we see the unfortunate

consequences of stress and breakdowns in chilling headlines. But

we tend to understand and sympathize with those who suffer from

these conditions. For Bishop Duggan, treatment and understanding

were evident in labels and institutionalization.

While there is no clear explanation why Bishop Duggan’s remains

were not moved with the other bishops in 1912, the stigma of mental

illness may have played a role. Societal attitudes toward the

mentally ill have changed since 1912 (many argue, not enough),

and it is time to recognize that Bishop Duggan did not do anything

wrong, but was the victim of an illness.

In his first eight years in office, he was an effective and diligent

shepherd for the church of Chicago.

He should be remembered as the fourth bishop of Chicago.

Treanor is archivist of the Archdiocese of Chicago.

Front Page | Digest | Cardinal | Interview

Classifieds | About Us | Write Us | Subscribe | Advertise

Archive | Catholic Sites | New World Publications | Católico | Directory | Site Map

|